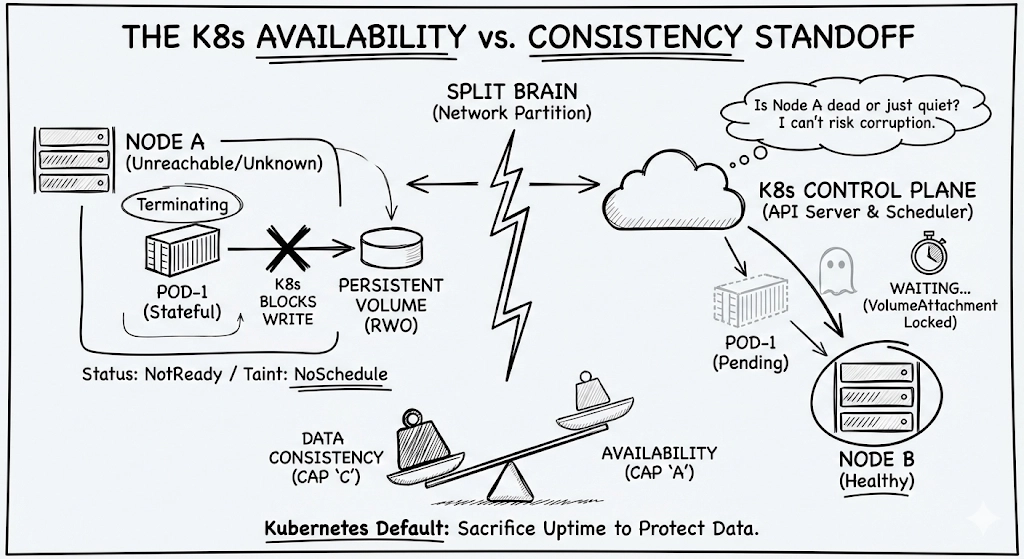

Your stateful pod sits in a 'Terminating' state, blocked by the same system that you chose to keep it alive. This is when you realize that Kubernetes doesn't actually care about your uptime; it cares about data integrity, and it will sacrifice your availability to protect it.

We often treat Kubernetes like a magic High Availability agent, and assume that it will always move workloads to healthy hardware. However, Kubernetes prioritizes data integrity over availability. When in doubt, K8s leaves your app down to keep your data safe.

This is a foundational part of how a StatefulSet works: it guarantees “At most one” semantic. No more than one pod to prevent data corruption.

Why the scheduler ignores your pod

The split brain problem

K8s doesn't know, and cannot know if a node is dead for real (for example, due to a hardware failure) or if the node is working but is not able to communicate back. This can lead to a split brain. Split brain happens when the network fails, and the cluster is split in half. Both sides think that they are the surviving healthy side. Why is it dangerous?

The danger of multi-writer

If Kubernetes would blindly reschedule the pod, two pods might attach to the same ReadWriteOnce volume: the existing pod, that Kubernetes thinks dead, and the new one just scheduled.

In this case, your data will be corrupted, due to the concurrent writing. To avoid that, Kubernetes adopts a very conservative default behavior.

Most databases are ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability): they would rather be offline than wrong. We tend to consider Kubernetes a BASE system (Basically Available, Soft-state, Eventual consistency). When a node goes dark, Kubernetes chooses the C (Consistency) in the CAP Theorem. It freezes your pod because it cannot guarantee that "Isolation" isn't being violated. The goal is for your data stays durable and uncorrupted.

The default behavior

As soon as the node is seen as unhealthy by Kubernetes, one of two standards taints are applied:

node.kubernetes.io/unreachable: this taint is added when Kubernetes cannot communicate with the node;node.kubernetes.io/not-ready: this taint is added when the node is actually reachable, but it reports that is not ready;

By default, every pod has a toleration of 300 seconds (5 minutes), to continue existing on a tainted node. You can reduce this time using tolerations, but it doesn't resolve the problem for stateful pods: because the node is unreachable, K8s has no way to confirm that a pod is actually dead. Pod might still be writing data to the disk.

Additionally, reducing the toleration is highly risky also for stateless pods: reducing the toleration too much leads to flapping in unstable network conditions, which is often worse than 5 minutes of downtime.

So, Kubernetes will move the pod to Terminating or Unknown, and it will stay like that forever. And trying to force a new pod in a new node wouldn't help either: the VolumeAttachment would remain in use by the dead node, so your new pod stays in ContainerCreating or Pending with an error in your events saying something like Multiattach error for volume <X>. Volume is already used by pod…

If K8s doesn't help, who will?

Application level replication

Databases, but also event queues, as Postgres, MongoDB, or RabbitMQ, should handle their own failovers. In a robust stateful setup, you don't just run one pod. You run a cluster, with a leader (Read/Write) and one or more followers (Read-only). Kubernetes task is only to run them, but it’s the application itself that manages data synchronization, and especially, the election of a new leader. How does it work?

The leader pod becomes unreachable

The remaining follower pods, on healthy node, fail to observe a heartbeat. They perform a vote, and promote a new leader.

The old “dead” pod is still stuck in

Terminating, but it doesn't matter, because it is now ignored by the application

For this to work, your application should share nothing: every pod has its own volume. In this way, K8s is not the data gatekeeper anymore, but the app itself is.

For example, Postgres doesn't know how to handle K8s failover. You can use Patroni, which is a “wrapper” around Postgres, that uses a Distributed Configuration Store (like etcd or Consul) to keep track of who is the leader. If the leader node's network cuts, the leader “lease” in the DCS expires. A standby Patroni instance sees that the lease has expired, and grabs it, promoting itself to primary.

MongoDB, on the other hand, is natively built for this. All MongoDB instances talk to each other constantly (with so-called heartbeats). If the primary goes down, the secondaries hold an election. Each MongoDB pod has its own persistent volume, so they don't need to steal the old disk from the dead node.

Node power off

You can also, manually or via automation, manually power off the “failed” machine. It can be a Virtual Machine or a bare-metal server: if it is off, it cannot write to the volume. At that point, you can force detach the volume, and you are sure that there won't be data corruption.

This is called fencing, or more colloquially, STONITH: shoot the other node in the head. Make sure that the problematic node is isolated and dead, so the integrity of the system is guaranteed.

While you can do this manually, the best course of action would be having automatic systems performing it for you.

CSI Drivers

Modern Container Storage Interfaces are getting smarter. Some of them can handle “fencing” a node by automatically invalidating its access to the disk. However, this is still far from being a universal “out of the box” feature.

Design for distrust

Start thinking about failure scenarios where a pod dies for good: how would your app react? While it is true that, for stateless workloads, scheduling is not a problem anymore, when there is data involved, you want to be prescriptive on how you want to manage data.

Kubernetes is a world-class orchestrator, but it is not a DBA. If your data is important, your database should be smarter than your orchestrator.

And, what are some of your firefighting stories about Kubernetes in the middle of the night?

Comments